Illustration by Dennis Mancini

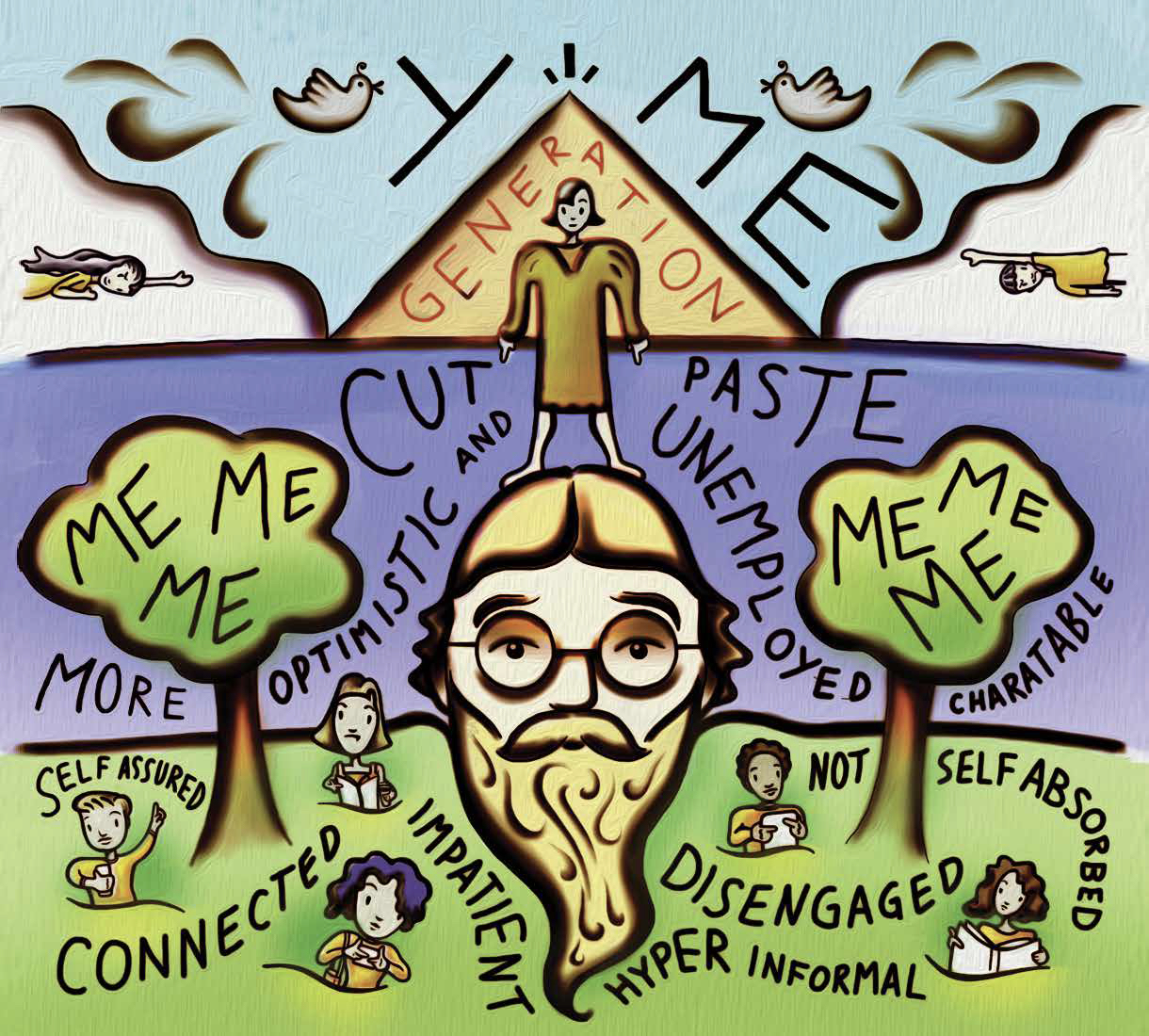

Generation Y | Me

This story appears in the Fall 2013 edition of Saint Mary’s Magazine.

Technology necessitates condensation. Elevator pitches are getting even shorter. We squeeze ourselves into dossiers, taglines and boxes as discomfiting as corsets. It makes the sweep of modern history more digestible, as the labels speak for themselves: the Greatest Generation begat Baby Boomers. Boomers begat Generation X. X begat Y; the Echo Boomers, the Millennials. And Z, the latest iteration, is safely parked in front of Grand Theft Auto V.

Except that “Greatest Generation” is rarely used as a pejorative and “Baby Boomer” has an alliterative oomph to it. Yet a number of professional and armchair sociologists—many of them Boomers—seethe at the very mention of Millennials. Among them is Dr. Keith Ablow, a FoxNews.com pundit for whom anyone between age 18 and 31 is “higher on drugs than ever, drunker than ever, smoking more, tattooed more, pierced more and having more and more and more sex, earlier and earlier and earlier.”

Dr. Ablow’s sentiments are supported by this year’s American Freshman Survey, a barometer of generational retrograde which revealed that Millennials’ collective self-image is at an all-time high—concurrent with significant decreases in aptitude scoring.

Time magazine dubbed it the “Me Me Me Generation.” News items excoriating—and the few that exonerate—Millennials are run as cartoons, mocking this much-maligned demographic’s fondness for animation. In numberless op-eds they are classed as the Cut-and-Paste Generation, the Status Update Generation, the Unlucky Generation. Homeownership is down among Millennials. They are postponing marriage, starting families later.

The kicker? They are more unemployed than any other age group—yet more optimistic and charitable, according to the Boston Consulting Group, which last year surveyed 4,000 Millennials between 16 and 34.

“Many of us will graduate with enough student debt to buy a house,” said Saint Mary’s student Jessi Bailey, “yet we still stay positive. I think our high opinions are a coping mechanism we’ve developed so we don’t have to truly feel the weight of the world we are just starting to come into.”

“I think our high opinions are a coping mechanism we’ve developed so we don’t have to truly feel the weight of the world we are just starting to come into.”

If you’re a Boomer who’s confounded by Millennials, join the club. General confusion around Millennial-speak abounds. Who are these fauxhemians who open artisanal mayonnaise shops, snapping Instagrams of their dinner? Is it possible they think they can save the world by sourcing foods locally, in lieu of a ten-cent tax on grocery bags? How is it that they can populate an Excel spreadsheet in such skinny jeans?

Like every generation, Millennials are without precedent: confident, change-oriented and connected on one hand; disengaged, impatient and hyper-informal on the other. They’re in abundance at Saint Mary’s, which appeals to students because it is decidedly not—as some universities are—an extension of high school. Through campus-wide service initiatives such as this year’s Great Bay Area Service Day for Schools—which drew nearly 800 volunteers helping out 21 area schools—Millennial Gaels find that they don’t crave vindication as much as a chance to disprove their reputation for narcissism.

“I think we’re trying to make the best of the world we’re currently living in,” said graduate student Chase Manning. “We still think we can save the world, and older generations take that as naiveté.”

Redefining the Generational Right-of-Way

Bailey and Manning are among those Millennial Gaels who are redefining the right-of-way. Last year, after volunteering in a soup kitchen, Bailey organized a rent strike to improve living conditions in an apartment complex in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. And Manning, who translated sensitive North Korean military communications for the U.S. Army, elected to use his G.I. Bill to write moral young-adult literature.

Like many Millennials who tune out the Dr. Ablows and Time cover stories—a means of self-preservation that many Boomers interpret as apathy—Manning finds the ad nauseam battering of Millennials in the news quite nauseating.

“How many of us have parents in their forties and early fifties?” Manning asks. “The Boomers were having their kids at an early age, too. Just because there’s a show called Teen Mom doesn’t mean it is the norm.”

Bailey concurs. “The media has exposed us to drugs, alcohol and sex starting at a young age,” she said. “I think it’s no surprise my generation is portrayed as out of control in many ways. But I think we are a product of the society that past generations have created for us.”

“It’s no surprise my generation is portrayed as out of control in many ways. But I think we are a product of the society that past generations have created for us.”

Bailey and Manning don’t presume to speak for their generation; they’re candid about the shortfalls they see among Millennials, among whom “humility is a rarity,” said Manning. And they acknowledge Boomer outrage as, if not wholly accurate, then certainly heartfelt. But in a hostile economy, at least to young job seekers, they have been obliged to bootstrap—and self-promote to degrees heretofore unseen—as they adjust to a credential-saturated job market, promising onerous and serpentine career paths.

“I can see how my generation can come off as having undeservedly high opinions of ourselves,” said Bailey. “I would agree that many of us do, [but] I think it’s a generalization because many of my friends are self-assured, not necessarily self-absorbed.”

It is evident that the multi-dimensionality of Millennials’ hopes (their desires for pay increases and promotions are interpreted by many Boomers as unearned entitlements) has spurred a phenomenon of aspirational multitasking, wherein young people today are managing the moving parts of their lives more effectively. While simultaneously training for Tough Mudders and juice cleansing and sleuthing for angel investors for their start-ups, Millennials are levering social media—including the usual suspects (Twitter, Flickr) and lesser-known platforms, such as Salesforce’s Chatter—to effect social change. Millennials’ use of these tools is something of a double-edged sword: slacktivism entered the lexicon after it became apparent that clicking “thumbs-up” on a Facebook profile and donating $10 to a cause via one’s mobile phone, while conscience-clearing, were insufficient salves to the world’s ills. It doesn’t help that the hyped-up sexting phenomenon—a dangerous and exploitative epidemic to some, a blasé aspect of modern dating to others—has obscured Millennials’ many worthwhile (albeit not uncontroversial) applications of technology, including 2011’s “Arab Spring” and “Kony 2012.”

To Manning, the vast potentialities of social media are linked to—but don’t necessarily inform—young peoples’ personal and professional goals.

“Millennials have a strong desire to make their lives worthwhile,” Manning said. “The problem is that they don’t always have the means or knowhow to do it. So they are stuck in jobs that they don’t really want to be in, stuck in a stagnant state of longing.”

Generational Gaps: Real or Conjectured?

Scant attention is paid to the elasticity—as in, the range of differences in technological comprehension, “gamer” intensity and celebrity obsessions—among Millennials as a whole. Anyone born in 1983 can recall the anguish of dial-up Internet speeds, while a current Saint Mary’s sophomore might be appalled that at one time cell phones were confiscated in high schools. Thirty-year-olds today likely wrote their college admission essays on their families’ first desktop, while 19-year-olds might have done so on one (or several) iPhones.

Millennials, when surveyed, say they crave mentorship but perceive the urgency of their motivation as intimidating to Boomers.

These gaps—especially with respect to technological usage across gender, racial and

socioeconomic groups—have warranted emerging research into how an entire generation can be not only so difficult to define—the consensus is that a Millennial is anyone conceived during the Reagan and Bush (H.W.) administrations, though even this is up for debate—but also so dissimilar.

The unlikenesses among Millennials pale in comparison to the generational tensions reported in the workforce. Millennials, when surveyed, say they crave mentorship but perceive the urgency of their motivation as intimidating to Boomers. According to PricewaterhouseCooper’s Managing Tomorrow’s People survey, Millennials also feel that older people insufficiently attempt to relate to the young, and are confused by their use of technology to create a personal brand—a strategy that Millennials use less to bolster their ego than to advance professionally.

Ultimately, the measure of the greatness of a generation is no longer obliterating atolls with H-bombs or attending Woodstock. In our data-driven age perhaps it’s not so surprising that Millennial is not only an -ism but that it’s apparently measurable.

The Pew Research Center quiz, “How Millennial Are You?”, yields individualized scores based on a 14-question cultural aptitude test, asking test-takers questions like:

- How important is living a very religious life to you personally?

- Were your parents married during most of the time you were growing up, or not?

- In the past 24 hours, did you play video games, or not?

- Do you have a piercing in a place other than your earlobe, or not?

- Do you have a tattoo, or not?

What one’s “Millennial Quotient” doesn’t help delineate are the fissures between the generations and their causes. One such difference Millennial Gaels identify between someone born in 1955 and 1985 is the way information is communicated—and this has resulted in several farcical efficiencies. For instance, we don’t retrieve our mail anymore: it retrieves us. Source code is the new poetry. Companies—such as San Francisco-based DODOcase—are disguising e-readers to look more like books.

Manners are also a concern, as many Boomers report feeling disrespected by Millennials.

“My generation tends to have a hard time saying ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ and ‘excuse me,’” said Bailey. “We don’t write thank you notes, and we don’t call each other. [We don’t] know how to send a professional email much less use phone etiquette, and that makes us sound rude when really we just weren’t taught how.

“We are a generation of communicating in 140 characters or less via Twitter,” she adds. “It shows.”

The Kids Are All Right

If there has been any decline over the years in students’ curiosity or engagement at Saint Mary’s, it isn’t apparent to theology professor Michael Barram. “Across the College there is a faculty and staff committed to engaging students in a way that will encourage them to ask big questions about life and their place in it,” he recently told the National Catholic Reporter. In agreement are the 93 percent of Saint Mary’s students who reported discussing their career plans with a faculty member in 2012, according to the National Survey on Student Engagement.

If Millennial Gaels are not anomalous, they still comprise an imperfect demographic. Millennials’ unconsciousness of intellectual property—evidenced by music piracy and plagiarism—and cursory understanding of American history—relative to Boomers’ and Xers’ grasp—does little to reassure older people today. Yet, if seen as a continuum, our present culture closely mirrors the culture(s) of yesterday(s). George Clooney is an inverse of Ronald Reagan; Destiny’s Child is a scantily-clad Andrews Sisters; New Direction is The Osmonds, sans Marie. It is also likely that Millennials’ ritualization of sex—much bemoaned and maligned by Dr. Ablow—comes in part from the pin-ups distributed to WWII servicemen under the guise that Betty Grable was the girl next door.

“We aren’t all selfish, arrogant, naive fools. Many of us haven’t given up on a brighter tomorrow. I know I haven’t.”

In this context it is likely that the “Average American” or “Main Streeter” in 1923 might have uploaded Gangnam-style parodies of themselves doing the Charleston on Vimeo; that Fitzgerald assuredly might have unfriended Hemingway on Facebook for the “poor Scott” reference in The Snows of Kilimanjaro; that Churchill would have rocked a Q&A on MTV.

So what really sets Millennials apart? It’s their immutable aplomb as impending custodians of households, industries, institutions. But this will only come to pass if they—if we—have a robust cheering section.

“If the Baby Boomers had more faith in my generation, I think we could get a lot more done,” Bailey said. “We aren’t all selfish, arrogant, naive fools. Many of us haven’t given up on a brighter tomorrow. I know I haven’t.”