Black Panther: a hero as brought to the big screen by director Ryan Coogler, whose journey into filmmaking began at Saint Mary's / Image courtesy Walt Disney Pictures and Marvel Entertainment

We Can Be Heroes: One Month Journeys of Inspiration and Making Music Videos

Ever wanted to learn about the roots or heroism, or explore the elements needed to make your own music videos? You’re in the right place. And we talk to two Saint Mary’s faculty about why it’s professors and not just students who love Jan Term courses.

Jan Term: the signature Saint Mary’s mini-semester that transports students across a variety of disciplines, ideas, and global locations that becomes a defining part of so many students’ SMC experience. While summer might seem a quirky time to think about January, the fact is that Jan Term is an important break from business as usual for both students and professors. Learning outside the box? Check. This year, while one group of students learned about the science behind cooking (making their own food along the way), others traveled to Denmark and Sweden to see firsthand why those countries rank as some of the happiest on Earth.

One of the ingredients in the secret sauce that makes Jan Term so popular at Saint Mary’s is the fact that SMC faculty love teaching the courses just as much as students enjoy the breadth of offerings. I sat down with a couple of those faculty to talk about what Jan Term means to them.

Professor of Theatre Daniel Larlham taught a course on the Hero’s Journey this Jan Term. Not coincidentally, that’s the course I took as a student. Then I sat down with Associate Professor of Media Production Jason Jakaitis to explore the Art of the Music Video through the lens he brings as a media professional.

Heroes, Heroism, and the Heroic

What defines a hero, and how do fictional heroes inspire real-life heroism? What is the significance of heroic stories in human history, and why might they be essential to the way people tell stories? Those are a few of the questions my fellow students and I explored in the 2024 Jan Term course The Hero’s Journey, taught by Daniel Larlham. Larlham has been teaching Performing Arts at Saint Mary’s for about a decade and was recently the recipient of a Fulbright fellowship in the United Kingdom. He saw Jan Term ’24 as an opportunity to discuss modern day heroism, specifically bringing awareness to heroic archetypes that already exist and have existed in popular culture far before the iconic Superman debuted in 1938. Building on his experience in the UK, last year Larlham wrote and directed a show about environmental activism that centered around heroism. That was part of the inspiration for this class as well.

“I’m still working through heroism and what it means in my own life,” says Larlham, reflecting on the course. “I hope that my students can start to recognize how heroism is around them all the time, encouraging them to maybe even live more heroically in an unembarrassed way.”

On being an expert

Most of the assignments were presentations that often required students to draw from experiences and people in their lives that they see as heroic. What was your reasoning behind this decision?

Daniel Larlham: I wanted students to feel like they were already experts about heroism, because they are. They're experts about it through their own experience and relationship with heroism, which differs from person to person. It's just a matter of bringing a more conscious awareness to it, and I feel like Jan Term allowed us to go to that place together because there weren't as many expectations about what’s right and wrong. There weren't as many disciplinary expectations, especially because everybody was coming at it from a different angle, because of their major or otherwise.

On Thinking Heroically

This course showcased a range of people and storytellers who have made an impact on understanding the psychology behind heroes, introducing authors like Joseph Campbell and Maria Tartar, who had dramatically different takes on heroism. How did you hope students might apply the information they learned in their lives?

DL: Living heroically may seem a little corny and perhaps delusional at times, but I think the archetype is much more fundamental than that. How might better understanding heroism shift your action in the world? What’s the course that you're setting for yourself in the world in terms of who you want to be in both a career sense but also on a daily basis? How can we work towards nudging the world in small ways to better incorporate those ideals?

“The archetype is much more fundamental than that. How might better understanding heroism shift your action in the world?”

—Daniel Larlham

Speaking for myself, heroes who are older or have suffered more tend to reach me more effectively because I have suffered in my own life. I've been humbled, and failed, and tried to keep going despite it. I find that more relatable now than I did when I was younger.

Moving on from Luke Skywalker and Superman

How has your feeling towards stereotypical heroic figures changed over time?

DL: Some of the stories I’ve known for years and years don't work on me the way they used to. I still feel echoes, but I'm no longer totally overpowered and possessed like when I was young. I think that as I've gotten older, I’ve developed my ability to connect with heroes and characters across different lines of identity. When I was younger, I was super fixated on the male heroes. Now I feel like I've been able to identify across different lines of ethnicity, race, gender, or culture, which has felt really freeing and eye-opening.

What other factors and/or experiences inspired you to teach this class?

DL: When I was young, those stories of heroism would overpower me to the point of feeling possessed, filling me with this energy that made me desperate to find ways of enacting heroism in the world around me. It was like, “Put me out there coach, who can I fight?” or, “Give me a lightsaber—what's the lightsaber in my life?” I think the idea that these stories have something in them beyond their surface material content and entertainment value that could provoke somebody to change or heal their psyche is really fascinating and inspiring.

The Art of the Music Video

While Larlham and his class investigated heroism, just across the Chapel Lawn, Professor Jason Jakaitis guided students through the Art of the Music Video, helping them learn about and create their own music videos. Jakaitis teaches in the new program in Media Production, which SMC students can choose as a major or minor field of study to develop expertise in multimedia production connected to a broad range of fields. For Jan Term, he teed up weekly music video assignments and led students to investigate some of the foundational history behind the genre. The class also highlighted how music videos are inherently collaborative.

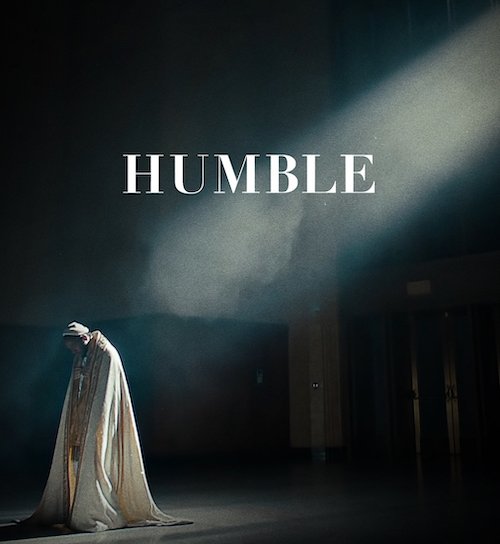

Filmmakers Scott Cunningham and Ewen Wright were a couple of the guest speakers, and students had the chance to ask them basic and complex questions about filmmaking. That included being able to tap Cunningham’s experience with big name music acts making award-winning videos, including MTV Video Music Awards for Best Cinematography (Kendrick Lamar’s “Humble” in 2017 and Shawn Mendes “Señorita” in 2019) along with two additional nominations (Ariana Grande’s “No Tears Left to Cry” and Camila Cabello’s “My Oh My”). And they had the chance to learn about Wright’s experience with eclectic artists including “stove-top folk” troubadour Gideon Irving, folk-meets-electronic-bagpipes project You Won’t, and alt surf rock duo Golden Age.

Accessible yet Challenging

What was your favorite part of teaching this class, and how did you build it so students of all skill levels could effectively engage with the content?

Jason Jakaitis: The class had this really wonderful mix of students who were making their first videos—one as a Biochemistry major, as well as students who had taken three or four of my production classes. What I tried to do was have the students that were more experienced sort of mentor the students that were less experienced. And there was a very low bar for technological engagement, too. We can use iMovie, or Adobe Premiere Rush. If they wanted to use their phones they could, but if they wanted to use the high end cameras I could tell them ‘We have those too.’

Over the course of four weeks, they made three different music videos. And then we spent a lot of time thinking and talking about the way in which music videos serve as a kind of playground for artistic and aesthetic development, and how they often discover new ways of visually communicating to audiences, while also exploring how those methods become integrated into the mainstream.

On the Techniques and History of Music Videos

What did you show students to help prepare them in making their own videos?

JJ: We talked about different styles of editing, and how, when you watch Hollywood films, you're raised on a certain style of editing called continuity editing, which preserves the illusion of a coherent and linear time and space. But music videos use the language of montage, which doesn't preserve that kind of space and time. You're jumping around between all these different places, and the cuts are totally bizarre, but somehow they work.

We definitely spent time talking about things like what’s considered MTV’s “Golden Age” in the ’90s, but we actually started a lot earlier, like looking at the music videos that The Beatles were doing. For example, when they were touring and couldn’t make it to the studio for television show performances, they would film themselves and send it in. Then we looked at stuff like Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” or Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” which were early moments in music video history that showed audiences how the song can actually become a secondary focus for the video.

On the Benefits of Experimental Art

What was the most surprising or exciting aspect of teaching this course?

JJ: When you start getting into the type of experimental art that music videos are, it's not usually something that you're born with. You're sharing creative work that you had to make on the fly. And it's tough, especially if it’s something you’ve never done before. It takes a lot of courage. But in a class like this, you get surprised about who brings something really interesting to class. It may not be the person who's always raising their hand. In most classes, you can usually see a correlation between talking in class and writing a good paper, but when it's experimental, sometimes people’s work can seem like it comes out of left field.

Also: What I love about filmmaking is that it's collaborative. It's your roommates, or a group of friends, all working together on a Saturday. It's not like poetry, or painting. I really wanted students to get a taste of that collaborative effort. Maybe after taking the class, it will motivate them to obtain a Cinematic Arts minor, or pursue filmmaking further—and that’s great.

Songs and Style: Student Music Videos

Here’s a sampling of music videos that students produced in the course.

Grace Greer ’25 — “Fly as Me” by Silk Sonic

Owen Johnson ’25 — “Low Rider” by War